The Art of Fugue performed by George Ritchie

The Art of Fugue performed by George Ritchie

The finest recording of Bach’s Art of Fugue irrespective of media or instrument

Gramophone Magazine

George Ritchie follows up his recordings of the complete Bach organ works with this magisterial performance of Bach’s late contrapuntal masterpiece The Art of Fugue .

The CD recording is accompanied by a generous selection of bonus tracks and, on the DVD, by a feature-length documentary and a detailed filmed lecture.

Featuring Christoph Wolff, Ralph Richards and Bruce Fowkes.

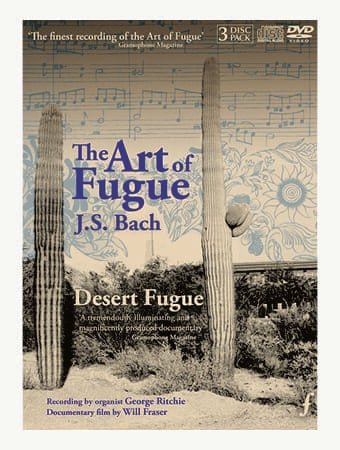

DVD – Desert Fugue

90 minutes

Historian Christoph Wolff, the Bach scholar of our time, and performer George Ritchie discuss Bach’s Art of Fugue and how it fits into the broader tradition of western music.

Organ builders Ralph Richards and Bruce Fowkes join the discussion when the subject turns to its suitability for the organ and the sort of instrument that Bach may have written his organ music for. The final section of the film is devoted to the Art of Fugue and Bach’s legacy.

DVD – George Ritchie’s Introduction to the Art of Fugue

111 minutes

George Ritchie gives a detailed introduction to all twenty movements of the Art of Fugue, discussing fugal techniques and playing dozens of musical examples, all illustrated with quotes from the Peter’s Edition of the score.

“Bach opens a vista to the universe. After experiencing him, people feel there is meaning to life after all.”

Helmut Walcha

George Ritchie studied with Helmut Walcha in Frankfurt in 1964-5.

George writes in his essay in the booklet accompanying our CD and DVD Art of Fugue set that Walcha, alongside Christoph Wolff, was one of the “two greatest single influences leading up to my recording of the Art of Fugue.” Speaking of one of Walcha’s performances of the Art of Fugue in Munich that year, George describes it as “one of the greatest musical experiences I have had.”

What made Walcha such a powerful influence on Ritchie was his deep understanding of counterpoint, the art of combining melodies. George says: “What drew Walcha to Bach was his appreciation of Bach’s art of combining melodies. The Art of Fugue is the culmination of the art of combining melodies, which in many ways is what western music has stressed more than anything else.” What sparked Walcha’s understanding was when, as a child and already almost completely blind, he was reading his sister’s piano book stave by stave. After working through pieces by romantic composers he came to the F major invention by Bach. He read the first stave first, but when he came to the second he discovered it was exactly the same but a bar behind, for the piece was a canon. From this moment the world of counterpoint in all its implications was opened to him.

Walcha made great strides as an organist, entering the Leipzig conservatory and becoming Gunther Ramin’s assistant at the Thomaskirche in Leipzig. Because of his blindness, his approach to learning music was to memorise each part, bar by bar, and then put it together with the next part. With instant recall he could play any part, soprano, alto, tenor or bass, from any bar in any of Bach’s organ works. He taught this approach to his students, who he might ask to play two parts of four part piece, leave out the third and sing the fourth, to develop their knowledge of the individual parts that made up the music, and to emphasise that knowledge of the music was at the centre of a good performance.

A nice illustration of Walcha’s approach is this recording of him rehearsing one of the slow movements from the f minor sonata for violin and harpsichord. He plays the harpsichord part and we can hear him singing the violin part, in the same way that he would ask his students to play one part and sing another. You can find the recording here:

In performance practice there have been many advances since Walcha’s recordings, some of which are now more than sixty years old. Phrasing, articulation, rhythm and the approach to registration have all undergone huge changes as scholarship has improved our understanding of how Baroque music was performed. For instance, George’s performances are very different to Walcha’s, and are considerably more well-informed in terms of performance practice. But though some aspects of Walcha’s playing now do not make historical sense, they always make musical sense. This musical authority stems from his extraordinary and intimate knowledge of the scores. It is this aspect of Walcha’s art that remains as important and as unsurpassed now as it was then, and it is this commitment to knowing the music from the inside out that was to George the most inspiring aspect of his study with Walcha.

The Unfinished Fugue

Walcha recorded Bach’s organ works twice between 1947 and 1977. Even among these legendary recordings, a particularly groundbreaking one was the recording of the Art of Fugue in 1954. This was Archiv / Deutsche Gramophon’s first stereo recording, and Walcha’s first from the organ of St Laurens, Alkmaar, an instrument that he became closely associated with and that he helped make famous around the world.

In this recording the final fugue is left unfinished; in Bach’s manuscript the music ends abruptly in bar 239. As we explore in the film, there is evidence that Bach did complete this final fugue, but that the final pages of the work have not survived. Whether or not this is the case, unfortunately the ending is lost.

This has sparked the imagination of many composers, and there have been numerous completions of the work, particularly since 1881 when Gustav Nottebohm discovered that the three subjects of the final fugue fit perfectly with the main subject of the whole work.

Walcha was a fine composer and improviser whose style, following on from Hindemith and others, was angular, modern and contrapuntal. Many of his students remember his improvisations on chorales at vespers at the Dreikönigskirche, or the spectacular fugues he would conjure out of thin air.

http://pipedreams.publicradio.org/listings/2007/0740/

Bach’s unfinished masterpiece piqued Walcha’s interest and he composed a completion that first developed the interplay between the three existing subjects of Bach’s fugue, and then, as per Nottebohm’s discovery, introduced as a fourth subject the theme of Contrapunctus I. The completion as a whole is dramatic and satisfying, including rhythmic vitality and some daring modulations.

Walcha recorded his completion as an addendum to his Bach recordings. But he used the Johann Andreas Silbermann organ of St Pierre le Jeune in Strasbourg, an organ that does not seem quite to suit his style, unlike the Schnitger organs of his earlier recordings, and I do not find it a very satisfying performance. As far as I am aware there are no other recordings of this completion.

Therefore, George Ritchie’s recording of Wlacha’s completion is a valuable reinterpretation of this piece. As the last track on George’s valedictory recording, this piece assumes a position of importance: it was George’s study with Walcha that provided much of the inspiration and technique with which to interpret the Art of Fugue; by recording Walcha’s completion George closes the circle and pays homage to his former mentor. The recording of the Art of Fugue as a whole is dedicated by George to Walcha, and this dedication provides the emotional core of the performance not just of the completed final fugue, but of the work as a whole.

Notes by Will Fraser

CD1:

Richards, Fowkes, & Co., Opus 14

Pinnacle Presbyterian Church, Scottsdale, Arizona

1 Contrapunctus 1; 3:52

2 Contrapunctus 2; 3:32

3 Contrapunctus 3; 3:47

4 Contrapunctus 4; 5:29

5 Contrapunctus 5; 3:45

6 Contrapunctus 6, a 4 in Style Francese; 4:50

7 Contrapunctus 7, a 4 per Augmentationem et Diminutionem; 4:15

8 Contrapunctus 8, a 3; 6:42

9 Contrapunctus 9, a 4 alla Duodecima; 3:56

10 Contrapunctus 10, a 4 alla Decima; 4:31

11 Contrapunctus 11, a 4 7:04

12 Contrapunctus inversus 12(1), a 4; 3:12

13 Contrapunctus inversus 12(2), a 4; 3:24

14 Contrapunctus inversus 13(1), a 3; 3:14

15 Contrapunctus inversus 13(2), a 3; 3:23

16 Canon alla Ottava; 6:08

17 Canon alla Decima in Contrapunto alla Terza; 5:23

CD2:

1 Canon alla Duodecima in Contrapunto alla Quinta; 4:40

2 Canon per Augmentationem in Contrario Motu; 4:49

3 Contrapunctus 14, Fuga a 3 Soggetti; 8:44

Additional Late Works

Taylor and Boody Organbuilders, Opus 9

College of the Holy Cross, Worcester, Massachusetts

4 Vor deinen Thron tret’ ich hiermit BWV 668; 4:14

Canonic Variations on Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her BWV 769a a 2 claviers et pedale

5 Canone all’ ottava; 1:44

6 Canone alla quinta; 1:43

7 Canto fermo in canone; 3:36

8 Canone alla settima; 2:31

9 Canon per augmentationem; 3:17

Bedient Pipe Organ Co., Opus 8

Cornerstone, Lincoln, Nebraska

10 Ricercar a 6 (from Musikalisches Opfer BWV 1079); 7:55

John Brombaugh & Associates, Opus 26

The Anton Heiller Memorial Organ

Church of Seventh-Day Adventists, Southern Adventist University,

Collegedale, Tennessee

Schübler Chorales

11 Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme BWV 645; 4:28

12 Wo soll ich fliehen hin BWV 646; 1:58

13 Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten BWV 647; 4:01

14 Meine Seele erhebt den Herren BWV 648; 2:34

15 Ach bleib bei uns, Herr Jesu Christ BWV 649; 2:44

16 Kommst du nun, Jesu, vom Himmel herunter BWV 650; 3:32

Richards, Fowkes, & Co., Opus 14

Pinnacle Presbyterian Church, Scottsdale, Arizona

17 Contrapunctus 14, Fuga a 3 Soggetti; 11:20

Completed by Helmut Walcha

© 1967 Henry Litolff’s Verlag / C F Peters Musikverlag, Frankfurt

£18.50